Blog

This blog was originally published on odi.org on 30 June 2025 here, and is reproduced with kind permission.

As global crises mount and aid budgets shrink, governments in developing countries are being increasingly pushed towards financing their own development. Domestic revenue mobilisation (DRM) - mainly through taxation – has become a critical lever for economic sustainability and resilience. Yet as DRM reforms have been slow and inconsistent, there’s growing concern: should aid still support DRM, and if so, how must that support change?

Back in 2015, the Addis Tax Initiative (ATI) was launched at the Financing for Development (FfD) conference in Addis Ababa, with donors pledging to double Official Development Assistance (ODA) for DRM by 2020. DRM then accounted for just 0.15% of total ODA- which was one fifth of what was spent on Public Financial Management (PFM)- the tax sector’s ‘bigger brother’. The idea was that in a world of what seemed like ever increasing ODA, spending more on DRM was an obvious way to support countries in their quest for fiscal self-reliance.

Ministers at the launch of the Addis Tax Initiative in 2015 (source)

Fast forward to 2025 and the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4) in Sevilla presents a stark contrast. The gap between development aspirations and the financing needed to achieve them has widened (an estimated $4 trillion for developing countries), and today’s donors face intense pressure to justify and preserve ODA budget lines. Yet the revised commitment again calls for doubling support to DRM by 2030, focusing especially on countries aiming to reach a 15% tax-to-GDP ratio, which some suggest represents a floor or a tipping point for greater fiscal sustainability.

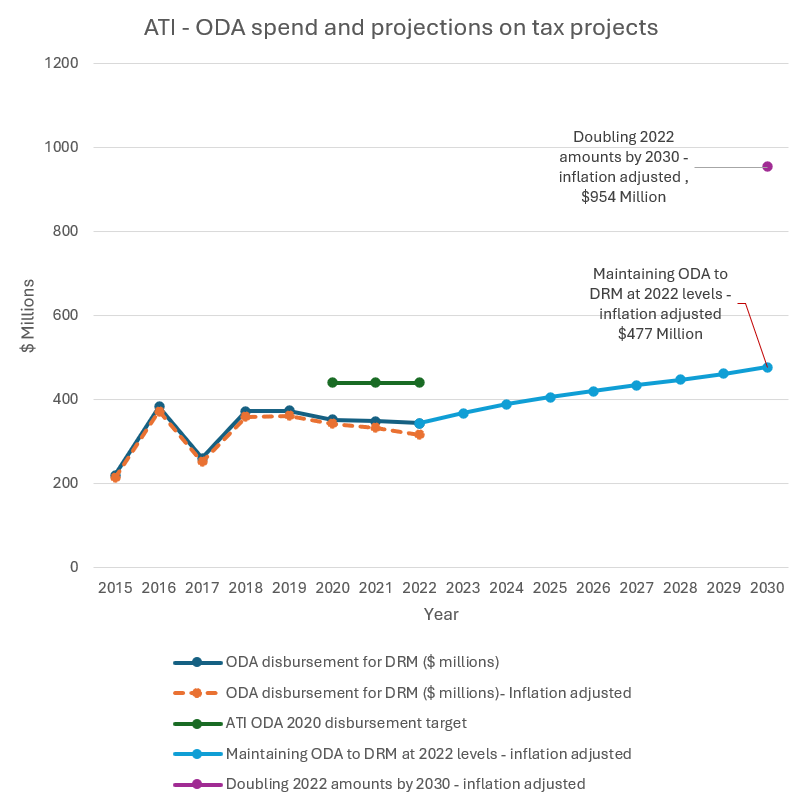

ODA for tax projects rose from $211 million in 2015 to a peak of $382 million in 2016, declining to $345 million by 2022—far short of the $441 million needed to meet the original doubling target. Adjusted for inflation and exchange rates, the gap is even larger. Philanthropies, which are not part of the ATI, have also dipped their toe in the water, investing in central programming and largely funding the tax justice advocacy groups.

Source: Addis Tax Initiative and authors’ estimations.

Note: The inflation forecasts are based on data from the World Economic Outlook (WEO) database.

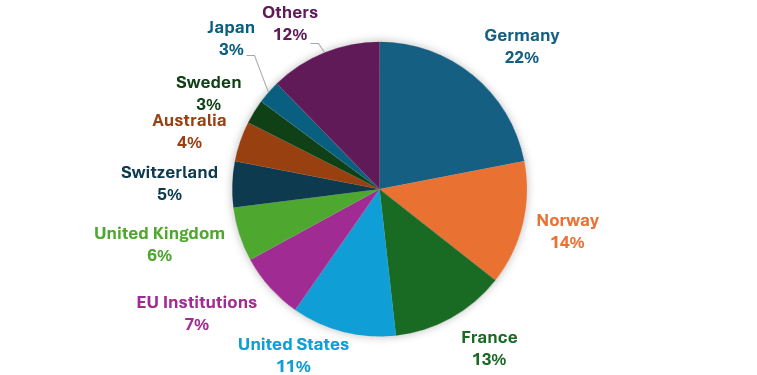

Missing the target is hardly surprising, given that resources have been diverted to deal with multiple crises and increasing national security threats. Projecting to 2030, in this context, reaching a real-terms doubling as has been suggested in some FFD negotiations, requires ODA to DRM to rise to $954 million (based on latest reported 2022 levels). Even maintaining allocations at real 2022 levels would necessitate an increase to $477 million. Moreover, with major donors such as Germany, France, the US and the UK all reducing ODA, even greater expectations will be placed on a shrinking pool of funding.

Source: OECD Data Explorer

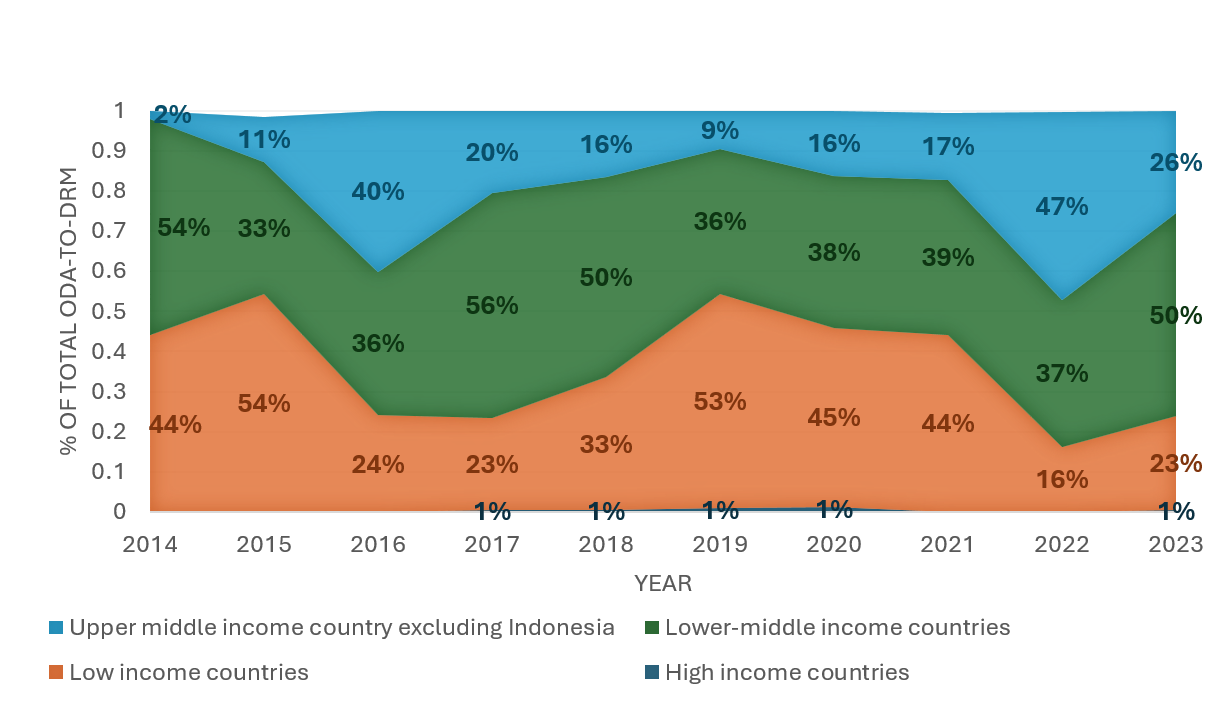

Based on high-level metrics, ODA for DRM is relatively well-targeted: the majority has been disbursed to low- and lower-middle income countries over recent years. Of total ODA for DRM, about 70% can be disaggregated to its contribution to individual countries. Analysis of these allocations shows that between 2014 and 2023, 57% of ODA to DRM was disbursed to countries with a tax-to-GDP ratio currently below 15%.

Source: OECD Data Explorer

Note: The figures exclude $502 million (28% of total) which was primarily ODA loans allocated to Indonesia during the period.

In the coming years, if FfD4 commitments are realised, we may see a further shift in disbursements towards these countries. However, the tax-to-GDP ratio is often not (and should not be) the key factor in determining where ODA for DRM will be most effective, particularly if the low DRM performance is by policy choice, shows low commitment to reform, or is too difficult to operate in, for example.

Even at double the 2022 amount, ODA to DRM would still represent a tiny fraction of overall ODA (approx. 0.3%). So why should donors invest in DRM rather than other sectors, such as health or education? Despite doubts—even public derision, such as Elon Musk questioning the value of a $17 million USAID tax project in Liberia—aid for DRM remains vital for several reasons:

Overall DRM results since 2015 have been uneven. Tax-to-GDP ratios (an imperfect, but often cited indicator of DRM performance) in many lower income countries has grown very slowly, stagnated or declined (see Figure 5). Available revenue data for 2021 identified at least 43 low- and middle-income countries that remain below the coveted 15% threshold. While some argue that there is significant unmet potential across developing countries, in practice, DRM performance broadly improves as countries develop, however, and tax reform takes a long time and involves a range of factors that are not well-reflected in the revenue potential estimates. As mentioned above, tax-to-GDP ratios in lower income countries have grown just 0.5 percentage points per year at best.

However, there are success stories. From 2010 to 2021:

Also encouraging are gains in tax efficiency:

Attributing DRM gains directly to ODA is difficult, not least because many factors affect a country’s decision and ability to implement reforms. We can point to evaluations of individual policy changes with measurable impacts on revenue or socio-economic outcomes, but few are able (or have investigated) the connection with ODA. Donors’ monitoring and evaluation of individual projects they invest in is, however, a crucial part of ensuring that ODA is used cost-effectively and further evaluation or meta-reviews would help take stock of what works in different contexts.

Evidence from individual ODA-supported reform programmes, while not clearly attributable to ODA, offers useful lessons and promising results, including:

Compared to the total amount of the $345m ODA spend on DRM, even these limited anecdotal estimates of impact suggest the potential for ODA to leverage substantial benefits across countries.

While there may be a strong case for investing in DRM, pressures of tightening aid budgets and domestic political pressures to prioritise alternative spending may make this difficult. FfD4 provides a key moment to reflect on the effectiveness of ODA, however, and many donors will be looking to achieve more with the investments they do make. While analysis of what works in each country may need further review, experience from historic and ongoing projects, such as those mentioned above, and ODI Global and IFS’s collective insights from 10+ years of TaxDev and other partnerships with low- and middle-income governments on public finance reforms suggest some opportunities for consideration:

1. Strengthening institutional capacity through partnerships

ODA should continue to support training, IT systems, compliance improvements, and data analytics. Partnerships—such as long-term research collaborations—can ensure ODA is driven by local ownership, as well as fostering innovation, context-specific solutions, and shared learning between countries.

A side event at FfD4 will explore how research partnerships can generate valuable insights for impact on fiscal policy and DRM.

2. Leverage technology thoughtfully

Digital transformation presents opportunities—e-filing, mobile payments, and data analytics—but it also brings challenges, a topic which was discussed at the FfD4 conference. Investments must be context-appropriate, supported by change management, and focused on generating actionable insights, such as better data governance and addressing capacity gaps in analysing the swathes of data that will be available. Tax data labs in South Africa, Uganda, and elsewhere offer models for replication.

3. Promote equity and inclusive growth

While for many countries mobilising revenue is paramount, ignoring the relative burden of that additional taxation misses the added potential benefits that improving the fairness of tax systems can have on both economic growth and future revenues (see Stiglitz (2012), Baselgia and Foellmi (2022), World Bank (2022), Grown and Mascagni (2024) and Støstad and Cowell (2024)). Yet less than 15% of aid-to-DRM projects explicitly include equity objectives. Moreover, reforms of income tax systems in Africa have reduced their redistributive capacity in recent years. ODA support for tools such as distributional analysis and policy formulation that considers the net impact of tax and social spending together, can ensure that tax policy is not just efficient but also fair.

4. Foster joined up, politically sensitive policy

In a fiscal squeeze, tax policy can be better designed to achieve more than just additional revenue.

Well-designed tax systems can help correct market failures, influence behaviour, and help underpin objectives such as labour market participation, innovation and job creation, energy transition and supporting healthier societies. Leveraging the combined impact of tax and spending can achieve a ‘triple benefit’, such as through earmarking of ‘sin’ taxes for financing school meals, or taking a holistic approach to addressing gender disparities.

DRM reform is also as much political as technical. Tax reforms therefore need to be informed by better evidence on strengthening tax policymaking processes, including political trade-offs, incentives, institutional and power dynamics. Adopting a more political lens can help governments, donors and civil society work together more effectively to deliver progressive tax reforms.

5. Encourage Regional and Global Cooperation

Harmful tax competition, tax avoidance and illicit financial flows cannot be tackled by individual countries alone. While expected impacts from a global minimum tax on multinationals has been weakened since its inception, automatic information exchange has supported a significant drop in offshore tax evasion, thanks to global tax cooperation.

ODA can support:

As called for by the FfD4 commitments, rather than scaling back, there is a strong case for doubling down—intelligently and strategically—on support for DRM. A modern, fair, and effective tax system is foundational to building resilient, fiscally sustainable, and equitable societies.

With the prevailing political and fiscal pressures, this will be challenging for donor countries to deliver. DRM performance across countries to date has been mixed and we need more evidence to really understand how ODA can work best in different contexts. But available examples indicate the potential for big benefits to be leveraged from relatively small amounts of ODA. With smarter targeting, better evidence, and stronger collaboration, ODA for DRM can help countries fund their own futures.

Published on: 1st July 2025

Print