Blog

The 4th World Bank Tax Conference exposed the magnitude of the challenge to build equitable tax systems and the progress achieved. Below is a summary of key findings presented at the conference.

Tax havens, offshore wealth, automatic exchange of information; these terms can appear opaque to the non-initiated, but understanding them is important—they refer to the vexing issue of international tax evasion and tax avoidance, which globally hinders the efficiency and equity of tax systems. This issue has gained prominence thanks to the release of micro-data from tax administrations, major data leaks (the famous Panama and Pandora papers), and pressure from civil society.

Simultaneously, research opening the black box of international tax optimization has exposed the large amounts of wealth and income escaping taxation every year. This is timely, as governments are under intense fiscal pressure and face concurring challenges; the recovery from the pandemic, weakening growth, investments to transition to a decarbonized economy, and, of course, rising inequality. The 4th World Bank Tax Conference exposed the magnitude of the challenge to build equitable tax systems and the progress achieved —internationally via the OECD/G20 inclusive framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS), and domestically via policies to improve compliance of the very wealthy. Below is a summary of key findings presented at the conference.

Shedding light on the magnitude of tax evasion, tax avoidance, and tax advantages benefitting the wealthiest individuals and largest firms around the world is a crucial step to raise awareness and encourage government action . Large enterprises often face lower effective tax rates: in firm-level tax returns from a dozen countries, the 1% largest firms benefited from substantially lower corporate tax rates than other firms in the top 10% of size due to their take-up of tax credits and tax exemptions (Bachas, Brockmeyer, Dom & Semelet 2022). Researchers must show creativity to measure what is purposefully hidden. Luminosity captured by satellite imagery provides accurate geo-localized measures of industrial activity. This new granular and high-frequency measure of economic activity is then compared with country-by-country profit reports of multinationals to estimate their potential profit shifting across jurisdictions (Bilicka and Seidel 2022).

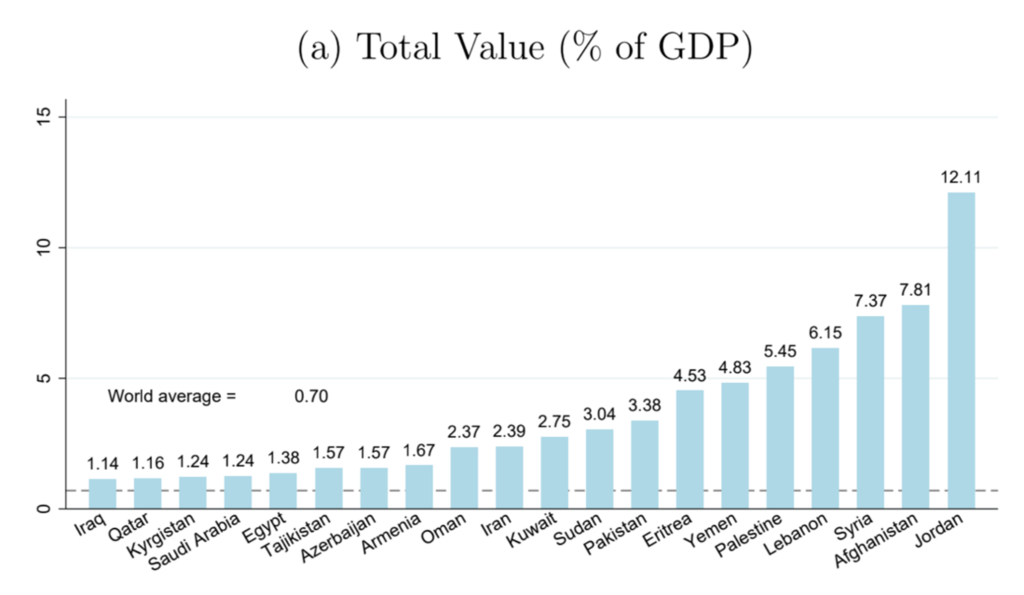

We also saw the importance of offshore real estate held in Dubai by foreign nationals: for some countries this represents over 5% of their GDP (Figure 1). Is this wealth reported domestically? This is unlikely, since even in Norway---where data could be cross-checked at the taxpayer level---only 30 percent of the Dubai real estate was reported in the mandatory wealth tax (Alstadsæter, Planterose, Zucman and Økland 2022).

Figure 1: Dubai Real Estate (2020), Relative to GDP: Top 20 Investing Countries

Source: Alstadsæter, Planterose, Zucman and Oakland (2022), Figure 6(a)

Note: Value of properties owned in Dubai divided by GDP, for the top 20 investing countries.

Recently, 137 countries members of the OECD Inclusive Framework agreed to set a 15 percent minimum corporate tax rate. The Framework also mandates automatic exchange of information (AEOI) across tax administrations to report on foreign nationals' bank accounts and financial assets. While the minimum tax agreement hasn’t yet come into effect, AEOI has been active across several jurisdictions for the past five years. Within the EU, cross-border account deposits fell in countries with stringent tax enforcement following AEOI, but part was relocated to countries with more opaque financial reporting (Casi, Mardan and Muddasani 2022). Further, AEOI on financial assets held in tax havens reduced the holdings of these assets, but a large share was reinvested in real estate. The United Kingdom’s market alone saw an 18 billion GBP rise in transaction values. Extrapolated worldwide, this implies that a quarter of financial wealth formerly held in tax havens was relocated to real estate and might continue to escape scrutiny (Bomare and Le Guern Herry 2022).

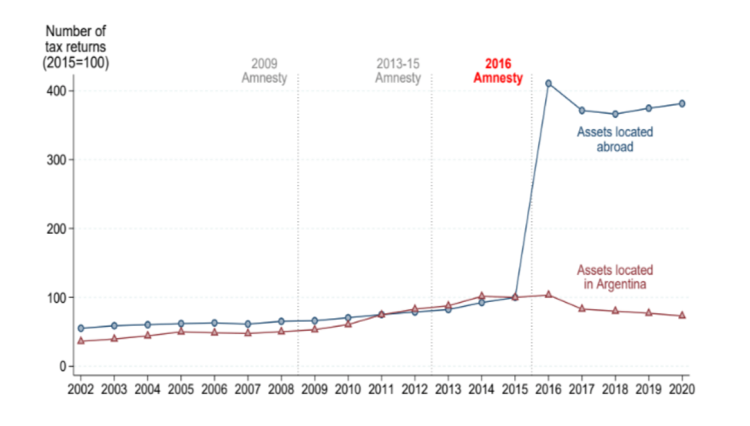

Lower-income countries like Uganda or Rwanda are also taking steps to increase tax equity, albeit with mixed results. The Ugandan tax authority established its first office dedicated to high-net-worth individuals via an impressive data effort to merge shareholders' records and property registries to income tax data. Unfortunately, it did not collect additional revenue (Santoro and Waiswa 2022). In Rwanda, the compliance of the richest taxpayers was assessed, and the country reformed its transfer of property reporting. However, the legal arsenal to prosecute non-compliant taxpayers remains insufficient (Kangave, Byrne, Karangwa 2020). There are positive examples: the 2016 tax amnesty in Argentina---which encouraged the disclosure of assets held abroad---led to the reporting of offshore wealth corresponding to 21% of GDP (Figure 3). The revenue collected financed an expansion of the pension system (Londoño-Vélez & Tortarolo 2022).

Figure 2: Taxpayers declaring foreign assets during tax amnesties in Argentina

Source: Londoño-Vélez & Tortarolo (2022), Figure 3.

Note: Number of taxpayers declaring assets owned domestically and abroad. The series is indexed to equal 100 in 2015, before the 2016 amnesty.

The momentum lends itself to cautious optimism: in the keynote, Gabriel Zucman noted that when he started documenting global hidden wealth a decade ago, nobody thought that tax havens would someday disclose financial information or that multinationals would face minimum tax rates. Evidence-based research can have an impact on changing how civil society and policymakers view these issues. But further research is needed to evaluate ongoing policies, combined with outside-the-box thinking on tax instruments designed for a globalized world. The final presentation provided a thought-provoking message: in online survey experiments conducted in multiple countries, citizens reported higher willingness to pay taxes when informed that their tax systems were progressive and lower willingness when informed that they were regressive (Hoy 2022). Progressive and just taxation is thus not only just but also crucial to sustain tax compliance and trust in governments.

This blog was first published on the World Bank's Let's Talk Development blog, and is reproduced here with kind permission.

Published on: 1st November 2022

Print