Blog

In July 2025, the federal and regional governments implemented the income tax amendment (Proclamation No. 1395 /2025) upon its approval by the House of People's Representatives. The reform aims to:

High inflation has pushed up wages and prices in recent years but income tax thresholds remained unchanged. This led to 'bracket creep', where inflation pushes employees/taxpayers into higher income tax brackets, increasing tax liability despite a lack of increase in real income. Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the average tax rates for individuals earning (as employment income) the equivalent of the GDP per capita. In Fiscal Year (FY) 2015/16, just before the 2016 reform, the monthly GDP per capita was around ETB 1,433. Those earning this equivalent at the time faced an average income tax of 12%. The 2016 income tax reform reduced the average tax rates for these individuals. However, the country's subsequent rapid nominal GDP growth drove average tax rates for people earning GDP per capita upward again to approximately 21.5% by FY 2024/25 (when GDP per capita had reached around ETB 11,000 per month). The latest reform, which came into effect in FY 2025/26, is expected to reduce the average tax rate for these individuals to 20% in its first year (red dashed line, 2025/26).

Figure 1: Average tax rates for those earning an equivalent of GDP per capita income

Note: The dashed vertical lines indicate the years in which the tax reform, including changes to the marginal tax rate, was introduced. The red dashed line indicates that it is based on projections.

Source : Authors' computation using World Bank data

Ethiopia operates a schedular personal income tax system, where different sources of income (such as employment, rental income and business income) are treated differently for income tax purposes. The exemption thresholds and tax brackets for employment income are set monthly, while for other incomes, these thresholds are set at the annual equivalent of the employment income thresholds.

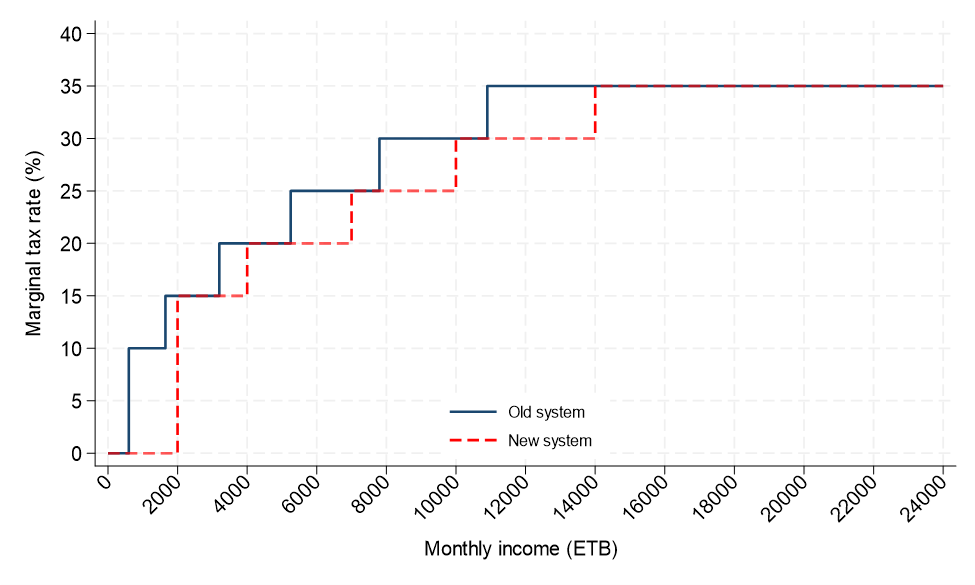

The reform revises income tax exemption thresholds and tax brackets upward. The employment income tax exemption threshold is raised from ETB 600 to ETB 2,000 per month; accordingly, the thresholds for rental income and other income are adjusted from ETB 7,200 to ETB 24,000 per year. The number of tax brackets is reduced from seven to six, removing the 10% marginal tax rate. The top marginal tax rate of 35% now applies to monthly employment earnings above ETB 14,000 and to annual rental and business income above ETB 168,000. Figure 2 compares marginal tax rates under the old and new employment income tax systems.

Figure 2: Marginal tax rates for employment income tax

Source: Authors' computations

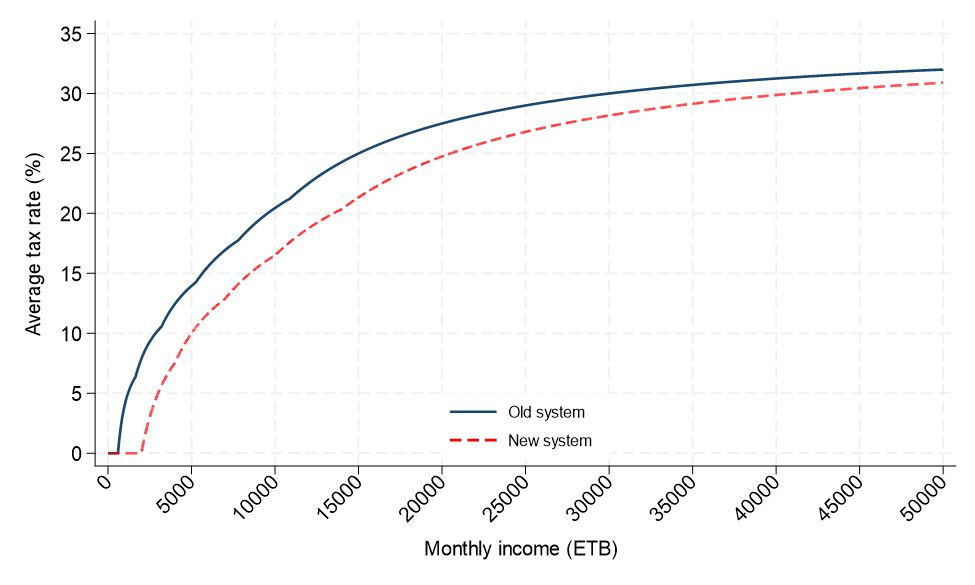

These changes to the personal income tax structure primarily aim to ease the tax burden on low-income workers, landlords, and small businesses without significantly compromising regional government revenue. Increasing the monthly exemption threshold from ETB 600 to ETB 2,000 reduces the average tax rate across the income distribution for all wage earners who previously paid any employment income tax (see Figure 3). For instance, those earning ETB 2,000 per month, who previously paid 7.9% of their pre-tax income in employment income tax, are now fully exempt, resulting in savings for them of ETB 158 per month (ETB 1,890 annually).

Figure 3: Average tax rates for employees by monthly earnings

Source: Authors' computations

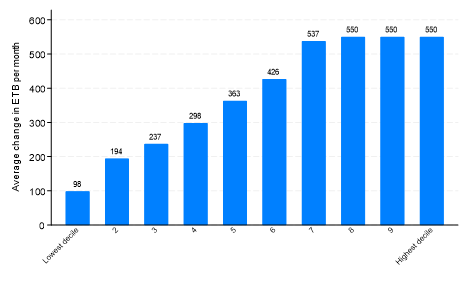

Individuals in the lowest-earning decile of the employment income distribution on average earn ETB 1,800 before tax per month. The reform yields a net average gain of around ETB 100 for individuals in this income group (Figure 4). Individuals with middling earnings (fifth and sixth deciles) gain around 400 ETB per month, respectively. Individuals in the highest decile, with average monthly earnings of ETB 55,220, gain on average approximately ETB 550 per month.

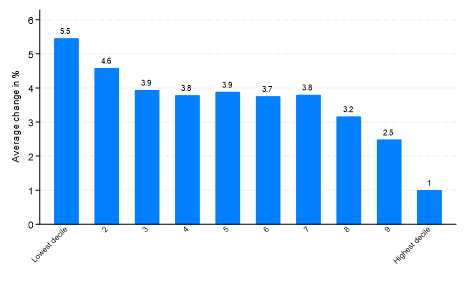

As a percentage of pre-tax earnings, the reform benefits lower-earning individuals most. The reform yields a net gain of approximately 5.5% of pre-tax earnings for individuals in the lowest-earning decileand approximately 4.6% for those in the second-lowest decile. The net gain then broadly decreases as the earning decile increases, as shown in the chart below. Individuals in the highest decile gain around 1% of their pre-tax earnings due to the reform.

Figure 4: Distributional analysis of the income tax rate changes (2024/25 earnings)

Panel (a): Change in net earnings in ETB per month by decile

Panel (b): Change in net earnings in % of pre-tax earnings

Note: Only includes individuals with positive earnings from formal employment. Results shown are shown for the 2024/25 earnings level.

Source: Authors' computation using the World Bank’s 2021/22 Ethiopian Socioeconomic Survey. Earnings are assumed to have grown at the rate of consumer price between 2021/22 to 2024/25.

While the reform eases the burden on low-income individuals, it also results in revenue loss, particularly for regional governments that depend heavily on personal income tax. Raising the exemption threshold further, as some stakeholders proposed, would have further eroded the already limited revenue base especially of the newer regional states. The reform strikes a balance between equity and fiscal sustainability, given the federal government’s limited capacity to offset these losses.

Under the current profit-based taxation system, many Ethiopian businesses report either nil profits or losses. In 2023, for example, about 17.1% of incorporated businesses filed losses in their tax return, while 26.3% reported zero profits in their return. This high percentage suggests that many businesses may overstate their costs so as to not pay tax, as would be consistent with evidence from other low- and middle-income countries. For instance, Lobel et al. (2024) estimate that businesses in Honduras on average overstated their true costs by around 13–17% to lower their tax liabilities. Best et al. (2015) find that due to evasion, a pure profit-based tax would raise 43% less revenue in Pakistan than a turnover tax with the same post-tax profits.

The reform introduces a minimum alternative tax (MAT) of 2.5% on businesses’ annual turnover, which will be applied on turnover when businesses' tax liabilities fall below this threshold and can be credited against future tax liabilities. This measure, widely adopted in other countries, has been shown to be effective in reducing the overstatement of costs and boosting government revenue. Countries that implement a MAT collect more tax revenue as a percentage of GDP than countries without MAT (Shoom et al., 2025).

In addition, digital services—activities that have become important to the economy—are now clearly defined for income tax purposes. The previous income tax law did not clearly define such activities, creating an administrative challenge for the tax authorities regarding how such income should be taxed. Now, businesses that derive income from any digital service provided in Ethiopia will be subject to income tax at a rate not exceeding 5% of their revenue, to be determined by the Council of Ministers.

The reform introduces a number of changes to simplify the taxation of small businesses. First, it reduces the number of taxpayer categories to two: 'A' and 'B'. Businesses paying presumptive income tax, previously classified as ‘category C’ taxpayers are now referred to as 'category B' taxpayers. The previous intermediate category B, which permitted the use of simplified bookkeeping, has been removed.

Second, the annual turnover thresholds for these two taxpayer categories have been revised upward. High inflation over the last few years had pushed many small businesses into a different category, resulting in substantial compliance costs for taxpayers and higher administrative costs for the tax authorities. Recognizing this, the reform revises the threshold above which businesses become category ‘A’ taxpayers from ETB 1 million to ETB 2 million, the same as the VAT registration threshold.

Third, the former presumptive regime for small and microenterprises was complex due to an overly-detailed sectoral disaggregation (99 sub-sector categories), each with its own presumed profit margin, and 199 taxable income ranges, making the system cumbersome and difficult to administer. The new reform simplifies the presumptive regime by introducing simple progressive tax rates based on annual turnover. To simplify the presumptive regime, the new income tax law also removed the Turnover Tax (which was payable in lieu of VAT); small businesses now only pay the presumptive income tax as per the new rate structure.

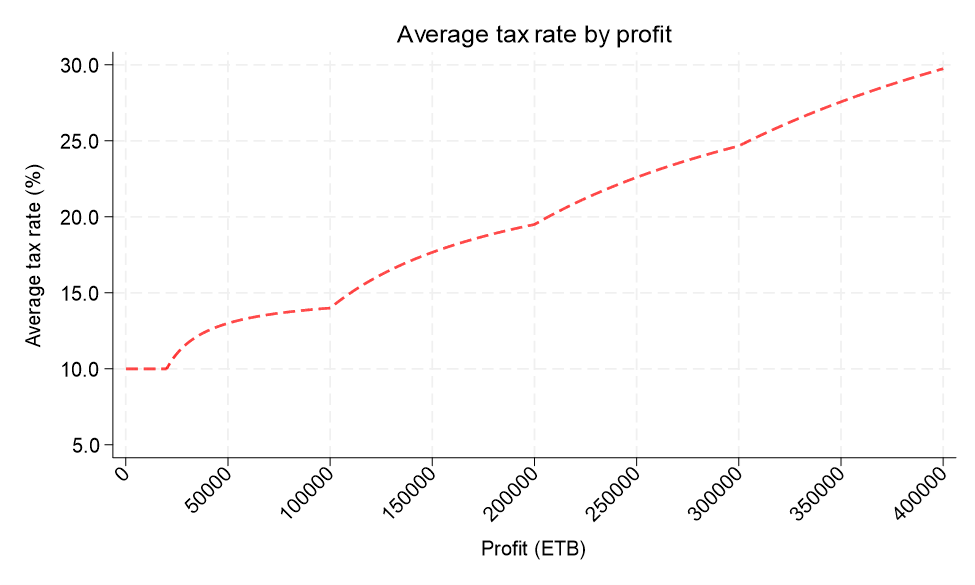

The marginal tax rates for the presumptive regime are designed to be comparable to the standard income tax schedule regarding average tax rates (Figure 5). For example, with a presumed profit margin of 20% for businesses under the presumptive regime, the average effective tax rates range between 10% and 30% of profits. A higher presumed profit margin would imply lower average effective tax rates; conversely, a lower presumed profit margin would imply higher tax rates.

Figure 5: Average tax rates for businesses under the presumptive regime (with a presumed profit rates of 20%)

Note: The average tax rates are computed assuming a profit margin of 20% across the sectors for the small and microenterprises under the presumptive regime.

Source: Authors' computations

The reform aims to ease the tax burden on small businesses, landlords, and low-earning employees without compromising government revenue too much, especially that of regional governments. Additionally, the complicated presumptive income tax regime for small and micro enterprises has been simplified. The turnover tax regime is removed altogether. To improve compliance with the business income tax, the new reform introduces a Minimum Alternative Tax (MAT) at the rate of 2.5% of turnover. Overall, the amendment aims to streamline the tax system and support the ongoing macroeconomic reform process.

References

Published on: 20th August 2025

Print