Project

Country: International

Inequality in developing countries is high and has not declined in the last decades (Alvaredo and Gasparini 2015). To what extent can tax systems redistribute income in these countries? At a first glance, their reliance on consumption taxes - viewed as regressive - to collect most of their revenue suggests a limited or negative impact on redistribution from the tax system. Yet, in practice, two channels could lead consumption taxes to have different impacts on poor vs rich households. The first is the “de facto” exemption of products purchased in the informal sector from taxation and the second is the “de jure” exemption of some necessity goods – in particular food items - which are often part of governments’ tax policy.

We combine microdata across over 30 countries and theory to quantify how these two channels affect the redistributive potential of consumption taxes and study what this implies for the design of consumption taxes, the main source of government revenue in developing countries.

We assemble a new micro dataset of expenditure surveys from over 30 low-and middle-income countries which contains information on the store type at the transaction-level. A major constraint in studying informality is that, by definition, informal sector purchases are hard to observe and to link to consumers’ incomes. We innovate by using the type of stores in which households report purchasing items -- ranging from home production, to street vendors, to supermarkets -- to proxy for consumption from the informal sector.

We then build a simple model to understand what these consumption patterns imply for consumption tax policy. The existence of informal varieties of goods which cannot be taxed changes both the efficiency and equity (or redistributive) characteristics of consumption taxes. It increases the efficiency cost of taxing consumption because households can substitute to informal varieties when taxes increases. It makes consumption taxes progressive as long as Informality Engel Curves are downward sloping. We calibrate the model for each country in our sample.

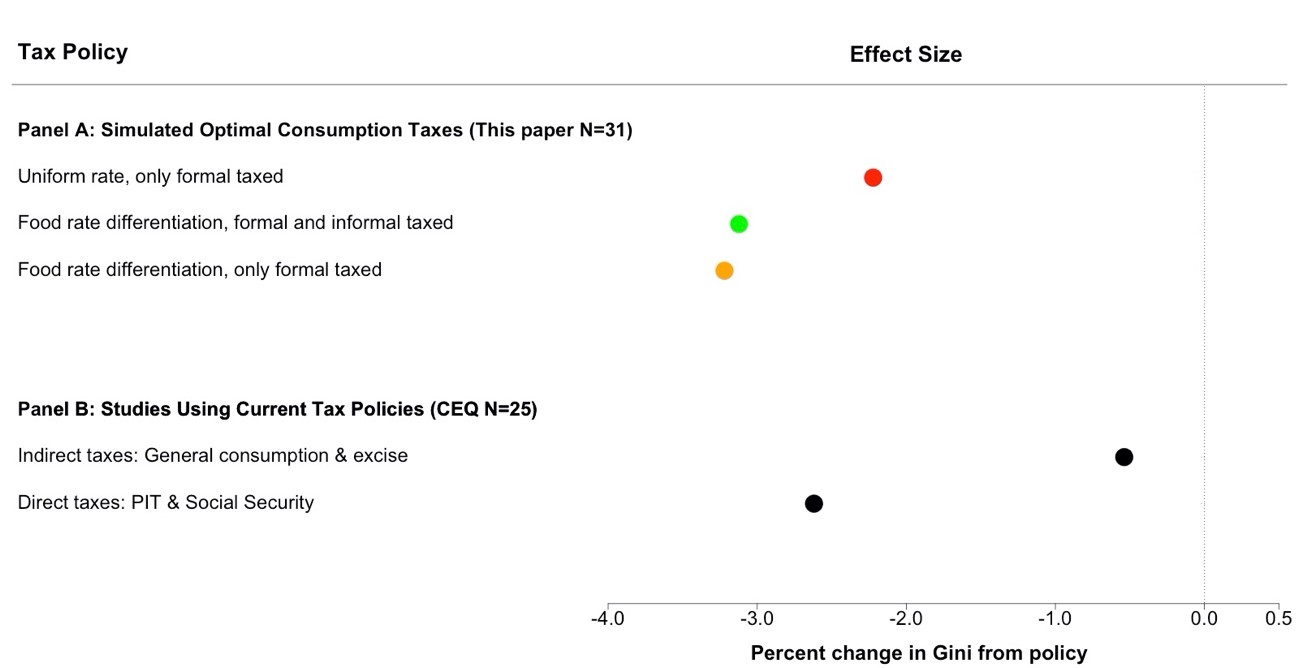

Finally, we investigate the impacts of consumption tax policies on income inequality by combining the calibrated tax rates with the household survey data and measure for each country the drop in the Gini coefficient due to different consumption tax policies.

We find that consumption taxes are substantially more progressive in developing countries than often considered. Indeed the optimal consumption tax policy is more redistributive than existing direct taxes (income and social security). Most of the redistribution gains from taxing consumption are due to the existence of large informal sectors and downward-sloping Informality Engel Curves; this result is robust to the indirect taxation of the informal sector in a VAT system (for example through the usage of formal inputs by informal firms).

Policies designed to increase the progressivity of consumption taxes, such as taxing food products at a reduced rate, are on the other hand fairly ineffective redistributive instruments.

These results caution that benefits from reducing the informal sector's size should be weighed against potential equity costs. More generally, tax enforcement policies should take into account not only their impact on efficiency but also on inequality. Finally, in most countries firms below a size threshold are exempt from taxation. This policy is often motivated by the large enforcement costs occurred by tax administrations when trying to tax these firms and the compliance costs to the firms themselves. The growing availability of digital technologies could lower these costs and make it possible to bring increasingly smaller firms into the tax net, removing the administrative rationale for exempting small firms from taxation. The results suggest that exempting small firms from taxation could still be justified on equity grounds.

We hope to share these results widely. Given that the sample includes 31 countries, we can calibrate our model of optimal consumption taxes for each of these countries for a discussion with the tax administration.

Published on: 13th September 2020